In this Winter/Spring issue, WHJ spotlights the Courtney Collins Fine Art Gallery’s Robert Osborn Collection with his intensely personal black and white portraits of Montana Native tribes people; oil painter Amber Down Blazina as she rediscovers the importance of trust and intuition; Iraq war veteran Jesse Albrecht who expresses conflict through his ceramic vessels; and Javier Moreno’s gallery showcasing his art alongside works from over 20 other artists.

These four uniquely compelling journeys into creativity, from the vibrant rhythms of contemporary painting to the subtle elegance of fine art portrait photography, to the evocative power of ceramic art, and the innovative examination of traditional mediums, illustrates the depths of human nature. Each article delves into the minds and methods of artists who shape our cultural mountain landscape, offering readers an intimate view of their artistic processes.

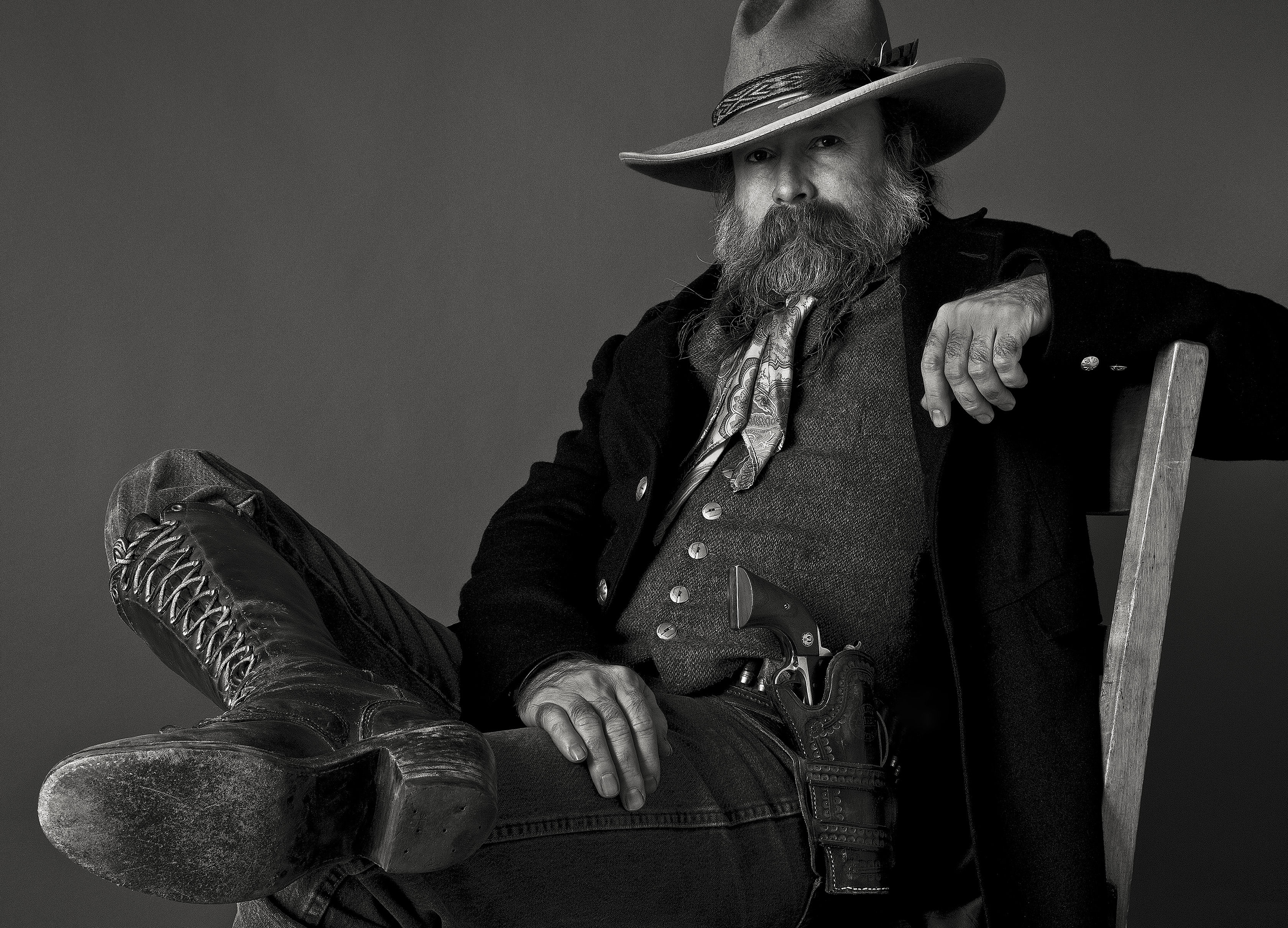

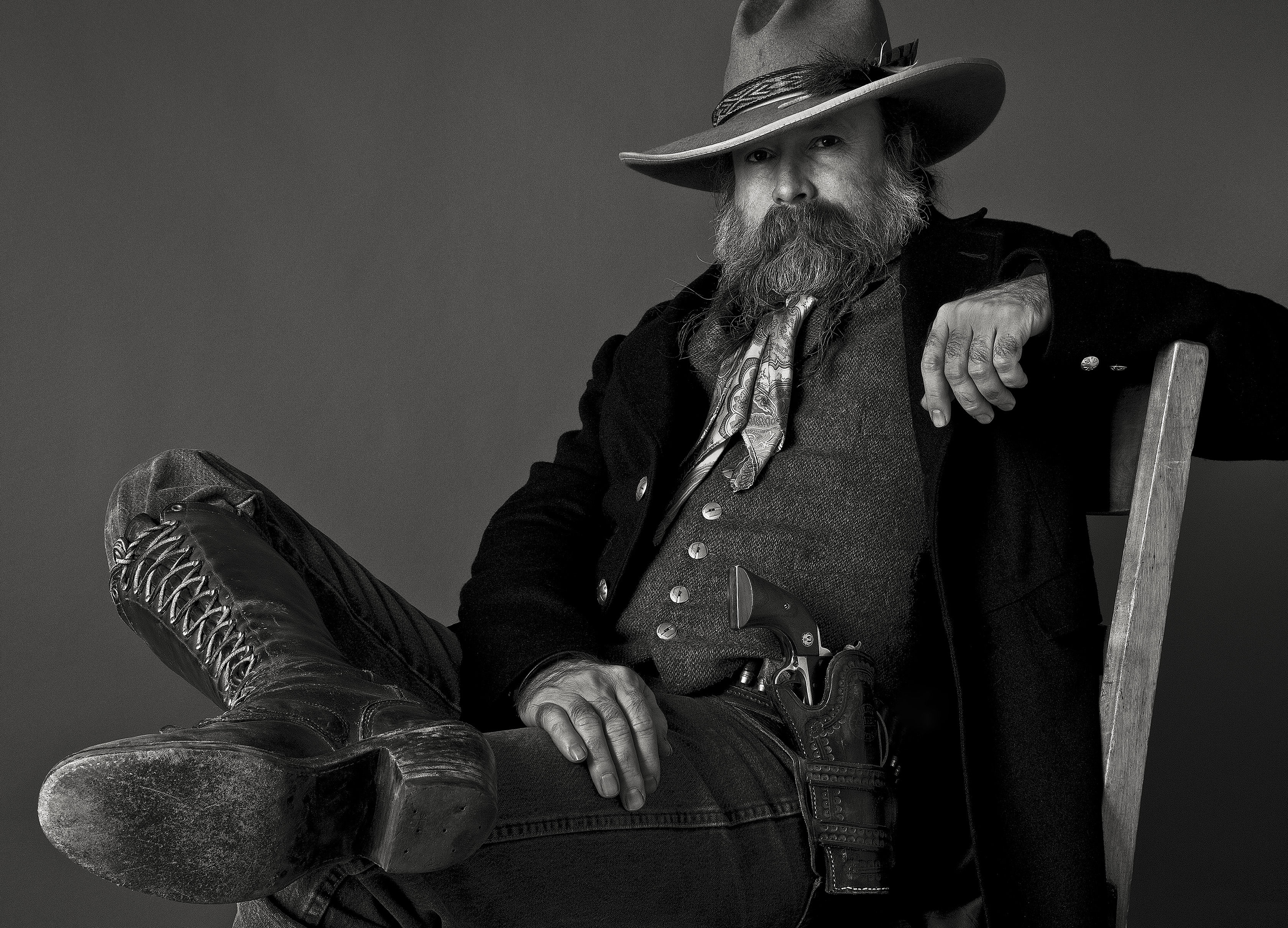

Brinna Battles Against Eagles, Apsáalooke, 2021 48” x 62” | Photograph | Robert Osborn

Now on display at the Courtney Collins Fine Art Gallery in Big Sky is a special collection of five large-format portrait prints by fine art portrait photographer Robert Osborn. “Robert wants to call it the Courtney Collins Collection,” gallery owner Courtney Collins says. “While I love the collaboration, I’m not sure the collection should have my name attached to it.”

To be fair, the five 48” x 62” prints included, printed as large as Osborn can print and frame them, were curated by Collins specifically for her gallery. Collins worked very hard at making a connection with Osborn and he’s been a presence in her gallery since she opened the doors in 2020. He’s had three private solo exhibitions there.

“The opportunity to work with Robert on this new collection of very large prints is extraordinary,” Collins says. “Now we’re at the point where we’re making these large-scale pieces together as a collaboration.”

Sometimes, it’s just the story of these portraits that entice clients to purchase the pieces. “I am able to sell his work without them even being on the wall in the gallery,” Collins says. “Clients know they can trust me.”

Reid Flatten, Saddle Maker, Livingston Montana 2015 | 48” x 62”

For fine art portrait photographer Robert Osborn, it’s all in the eyes. That’s where he can read through the pain, sorrow, pride, and joy to find the essence of humanity within a person. Over the last decade or so, Osborn’s passion led him to Montana Indians, the homeless, and cowboys. He shoots and prints in black and white, so the distraction of color falls away. Instead, light and shadow play against each other to heighten the subject. Think Italian Renaissance’s chiaroscuro; think Caravaggio. That kind of honesty catches the viewer by the throat.

Osborn’s portraits create narratives. They tell stories. Reveal uneasy truths. The astounding component of his portraits are the expressions that live under the skin. Absent are the toothy smiles or over-adorned sittings. Instead, he teases out individual lives, expressed through the eyes of his subject. What he calls the soul of a person.

John Hoiland No 18, Hoiland Ranch, Montana 2016 | 48” x 62”

“The person walks in and knows they’re going to be photographed,” Osborn says. “They’re very self-conscious. Everything I’m trying to do is to get past all the facades, I want to get past the self-consciousness. I want to get to that real person. Now we can start taking the picture.”

Everything in the composed portrait begins in service to the eyes.

As Osborn begins to work with his sitter, a kind of subtle connection takes place. Whether the person is homeless, dealing with addiction, or has survived a tough life, Osborn seems to reach across time, to find that pureness, that untouched beauty that lives within each of us.

Cameron Chaske, Spirit Lake Dakota Sioux, Frazer, MT 2019 | 50" X 40"

“My imagination opens up and I begin to see that person—their heart and soul—and I see the life that led up to this point,” Osborn says. “I begin to see almost a bigger than life version of the person, be it a cowboy, a Northern Plains Indian, or a street person; I begin to see that image on a kind of a monumental or iconic scale.”

It is this kind of empathy that allows Osborn to connect with his subjects. “The viewer understands addiction, the viewer understands alcoholism and drug use, and the attraction of those things,” he says. “They understand despair. They un-derstand all of the human things that are going on as they stand there in front of the photograph. If it’s a really good portrait, as they stand there, they realize that they’re only a few degrees, a very few degrees, re-moved from those situations, are thinking but for the grace of God.”

Just approaching a stranger to take their photograph takes courage, but Osborn does more than snap an image. His honest and open nature, combined with the work ethic of a rancher, often is the deciding fac-tor with people.

When working with his subjects, Osborn steps outside his own comfort zone. “It’s almost like I have to climb into their box,” he says. “If I photograph a homeless Indian person on the Fort Peck Indian Reservation, if I don’t go into it with them, as much as I’m capable of going into the depths of homelessness and the despair and the alcoholism and drug addiction and the poverty and the freezing in the winters and being ignored by everybody as if they are invisible, how in the world am I going to get a picture of the heart and soul of a homeless Indian person?”

Once a photo session starts, it’s not just Osborn, a backdrop, and some lights. “There’s a whole new dynamic,” he says. “It is me and this person or culture or history but it must but there’s something right … there’s something about me and there’s something about him that creates that bond.”

Osborn’s openness, courage, and ability to become intimate with another person allows that person to be vulnerable for a moment. It’s that moment Osborn catches, like a firefly in cupped hands, and just as delicate.

“There’s respect, too,” Osborn says. “I do this instinctually, because I don’t want it to become a tool and it would be inauthentic if I did that.”

Currently, Osborn’s retrospective is on view at the C.M. Russell Museum in Great Falls, where his work spans more than 70 years. He’s also had shows at the Bozeman Art Museum and other museums of note around the region. However, the only gallery he works with is the Courtney Collins Fine Art Gallery in Big Sky.

As in most things, relationships take nurturing. In the case of artists and galleries that is doubly true. To have these opportunities with artists takes a lot of work and time. Moreover, one must earn it. “It’s an absolute honor for me to be representing him. I’m selling museum-quality work. I’m just so proud to hang these portraits here,” Collins says. “Robert will always hold space in my heart. And what a professional achievement for me. I am also considering naming my new rescue dog ‘Osborn’ after him.”